An incognito visit (hahaha) to the University of Edinburgh.

An incognito visit (hahaha) to the University of Edinburgh.

And now, since the end is near :), I want to write a bit about the last Wagner’s operas: Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal. Surely, we understand that in Der Ring, Wagner critiques the gods and rulers who perpetuate cycles of oppression and greed, reflecting his anarchist ideals; while in Parsifal, the knights’ spiritual decay mirrors the moral failure of religious and political institutions, tying to Wagner’s later disillusionment with worldly systems of power. But there are also ethical and philosophical relationships between Der Ring and Parsifal that charts Wagner’s evolution from anarchist-revolutionary to Schopenhauerian-mystic.

We might think that Der Ring and Parsifal are polar opposites in Wagner’s moral universe. The Ring is a story of power, will, and desire, where the ethical conflict revolves around the corrupting nature of power (embodied by the ring itself) and the human compulsion to control nature and fate. Alberich’s Promethean spirit of control and domination, and Wotan’s pursuit of divine order complicated by his own law and ambition, leading to a cycle of betrayal and ruin. On the other hand, Parsifal represents a spiritual counterpoint. Its mysticism emphasises grace, compassion, and redemptive purity. While Der Ring charts a descent into chaos through greed and power-lust, Parsifal seeks salvation through self-abnegation and the renunciation of worldly desire. Parsifal as the “the fool” achieves wisdom through innocence, not knowledge or power. This evolution actually resulted from Wagner’s discovery of Schopenhauer’s doctrine that true liberation comes not through the assertion of will, but through its negation.

Wagner’s anarchist phase (influenced by figures like Bakunin and the revolutionary spirit of 1848) infused his early concept of the Ring with ideas of liberation from tyranny and critique of power. Wotan is, in a sense, the ultimate “failed anarchist” — his efforts to create order (through laws and contracts) lead to his own entrapment, mirroring the anarchist critique of the state as a mechanism that inevitably becomes self-perpetuating. Wotan’s despair reflects Wagner’s recognition of the cyclical nature of power and the impossibility of genuine freedom within systems of control.

However, after Wagner’s discovery of Schopenhauer, his concept of ethical heroism shifted. Schopenhauer’s pessimism argued that life is suffering, driven by blind will, and the only escape is through the negation of that will. This had profound consequences for Wagner’s art. The Ring concludes not with liberation (as early anarchist Wagner might have imagined) but with Götterdämmerung — a total collapse of the system, not a revolution but an apocalypse. In Parsifal, however, Wagner envisions a more Schopenhauerian “redemption through compassion.” Amfortas’s suffering is finally healed not through heroic deeds, but through Mitleid (compassion) — a key Schopenhauerian virtue. This shift from heroic rebellion (Ring) to quiet renunciation (Parsifal) mirrors Wagner’s philosophical evolution.

The anarchism of Wotan’s rebellion gives way to the Schopenhauerian submission of Parsifal. Where once Wagner celebrated the Sturm und Drang (storm and stress) of the world, by the time of Parsifal, he embraced an otherworldly quietude.

Now about the theme of innocence. The figure of the innocent hero reoccurs across Siegfried, Parsifal, and even Lohengrin. Siegfried, as the wild child raised by Mime, embodies natural, untamed innocence. He is fearless, unburdened by history, and initially untainted by the corrupting influence of power or love. However, Siegfried’s innocence does not lead to wisdom but to his destruction. His ignorance of deception (betrayal by Hagen and even Brünnhilde’s eventual disillusionment) seals his tragic fate. Parsifal, by contrast, follows an explicitly spiritual and redemptive arc. Described as der reine Tor (the pure fool), Parsifal’s innocence allows him to overcome the forces of desire and temptation. It is a form of “higher innocence” — a purity that remains even after worldly trials. Unlike Siegfried, who succumbs to deceit, Parsifal achieves higher wisdom precisely because of his innocence. This innocence allows him to perceive the hidden suffering of Amfortas and ultimately to heal the King and restore the Grail. Wagner seems to suggest that innocence, when preserved as a form of higher insight (as in Parsifal), allows for salvation; while innocence that remains mere ignorance (as with Siegfried) or innocence that succumbs to doubt (as with Elsa) leads only to tragedy.

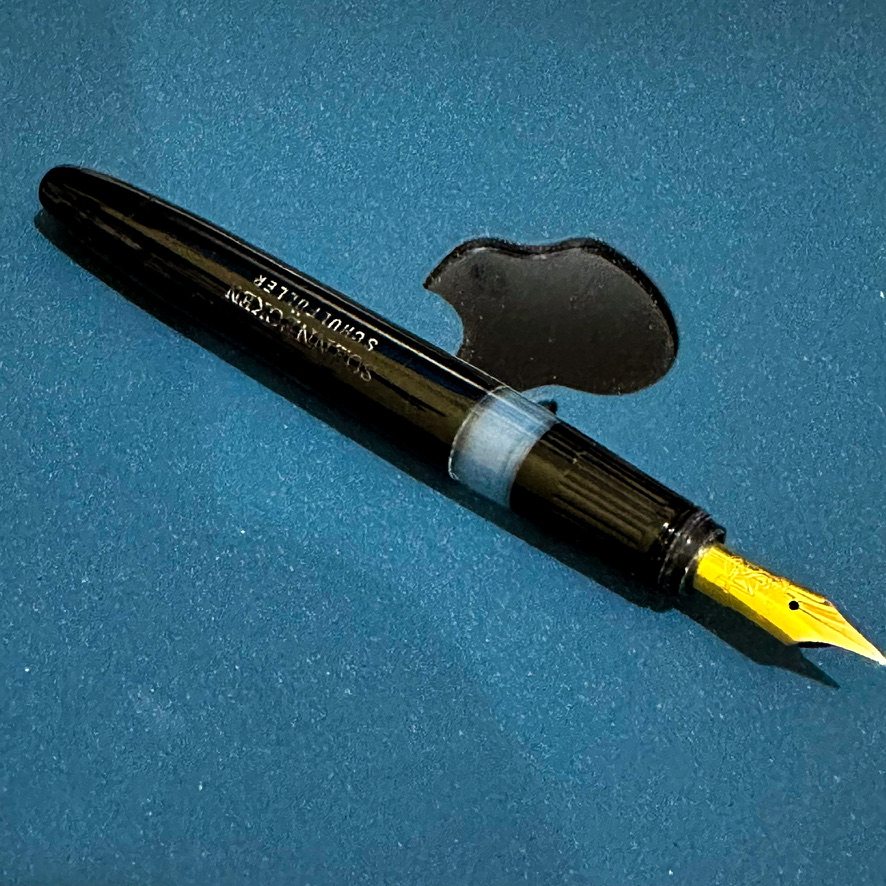

Happy Fountain Pen Day! Fountain Pen Day is celebrated on the first Friday of November. But what is so interesting with this classical instrument?

The history of fountain pen must start with the long development of writing instruments, including quill and qalam. But the modern fountain pen we know today was first patented in 1827 by Petrache Poenaru, a Romanian inventor. However, it wasn’t until the 1850s that fountain pens became popular, thanks to the innovations made by Lewis Waterman. Waterman developed a system that used capillary action to control the ink flow, which prevented leaks and made writing smoother and more consistent. He also created a reservoir system that allowed the pen to hold more ink and made refilling easier. These innovations helped fountain pens become more reliable and convenient than earlier models.

The popularity of fountain pens continued to grow throughout the 20th century, as new designs and materials were introduced. In the 1920s, the first ballpoint pen was developed, which threatened to replace fountain pens as the preferred writing instrument. And the digital era have virtually erased the necessity of fountain pens from our society. Today, fountain pens are only used as a symbol of sophistication and elegance. They are often used for signatures, calligraphy, handwriting, and personal expression.

I started using fountain pen when I was an SMP student. I was a quite diligent student and writer, so I wrote too much. Instead of having to buy too many ballpoints, I chose to use my father’s unused Ero fountain pen, and just fill it with ink from a big bottle of Parker’s Quink at my father’s desk. My brother also influenced me to buy an Ero “two in one” pen — a single instrument with a fountain pen nib and a ballpoint. Needless to say, my memory of my SMP time involved continuously colourful hand, spilt by the blue, red, purple ink.

After digital era, I just use fountain pens occasionally. Buying ink was also weird, when almost all communications are established using computers and mobile devices. Just somehow I tend to get interested in using manual or semi-manual technology. And that’s the reason I still use fountain pens, albeit occasionally.

Despite the convenience and ubiquity of digital devices, many people still prefer using fountain pens for a variety of reasons:

During the Covid-19 pandemic, besides creating and doing important things for the nation (trust me, haha), I also spend more time to maintain, use, and add the collection of my fountain pen. Please visit my fountain pens collection here: https://pen.dance; and let’s dance with my pens.

Returning in the afternoon, I stretched myself, dead tired, on a hard couch, awaiting the long-desired hour of sleep.

It did not come; but I fell into a kind of somnolent state, in which I suddenly felt as though I were sinking in swiftly flowing water. The rushing sound formed itself in my brain into a musical sound, the chord of E flat major, which continually re-echoed in broken forms; these broken chords seemed to be melodic passages of increasing motion, yet the pure triad of E flat major never changed, but seemed by its continuance to impart infinite significance to the element in which I was sinking.

I awoke in sudden terror from my doze, feeling as though the waves were rushing high above my head. I at once recognised that the orchestral overture to the Rheingold, which must long have lain latent within me, though it had been unable to find definite form, had at last been revealed to me.

I then quickly realised my own nature: the stream of life was not to flow to me from without, but from within.

– Richard Wagner: 22 May 1813 – 13 February 1883

When we talk about elegance, usually we refer to designs: product, web, programme, etc. But, while we’re in it, we can discuss about elegance in life: how to set the maximal simplicity to our way of life, while maintaining the highest performance possible in it.

Life is beautiful, right?

© 2026 Kuncoro

Theme by Anders Norén — Up ↑